One of the most overlooked aspects of boating safety is local knowledge.

That goes for boaters and rescuers alike. Just ask Tony Polkoski and the Florida tow boat captain who saved his life, Carlos Galindo.

Carlos owns Islamorada TowBoatU.S. with his wife, Ilene Perez. He’s been helping mariners get out of trouble in the Florida Keys for nearly 30 years. Most of his calls are for accidental groundings or engine trouble, but occasionally he finds himself in a life-or-death situation.

Such was the case last March when Ilene monitored a mayday call on VHF Channel 16. While cutting through a zip tie to release his outriggers, Tony had severed the artery in his left wrist. He was bleeding uncontrollably, and now his wife Shawna was calling for help. The panic in her voice told Ilene all she needed to know. She told Carlos to go, and as a Coast Guard response boat roared toward the Humps, he was close behind.

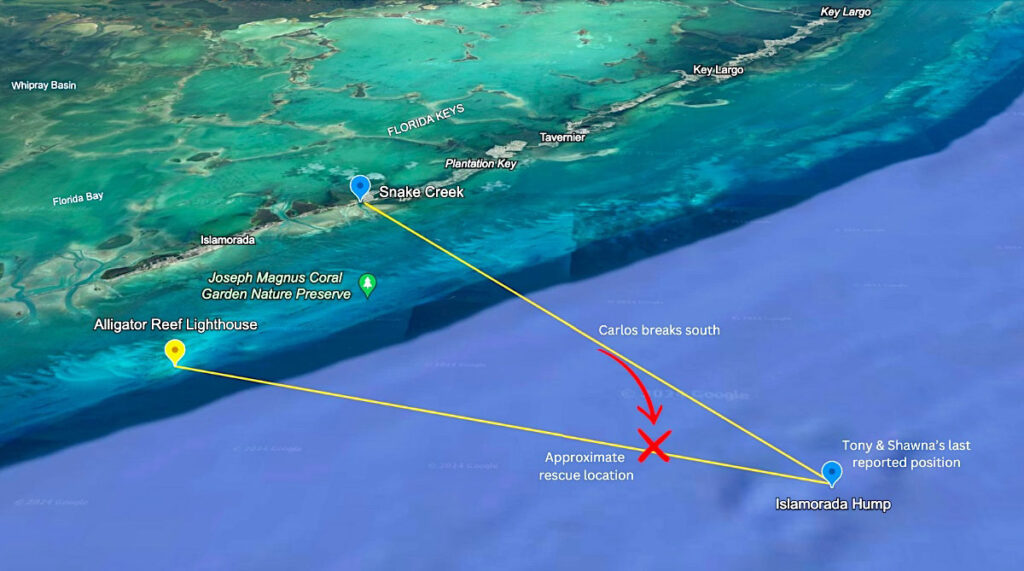

Shawna didn’t know her precise coordinates, just that she and Tony had been fishing the Islamorada Humps, a patch of shallow waters and fishy rips about 14 miles southwest of Carlos’s home port of Snake Creek, Fla.

As Carlos ran full-throttle toward the Humps, he had time to filter what he had heard on the mayday call through his knowledge of the waters off Islamorada, and how boaters – especially inexperienced ones – react under stress.

“When you listen to the radio for so many years, you’re always trying to listen to what’s in the background,” Carlos says. “And this call here, I could hear the lady talking about the Humps, but I could also hear the engines running at high RPMs. That told me she’s not going to be at the Humps. No way.”

The next question was if Shawna and Tony were not at the Humps, where would they be? Carlos had a hunch about that too.

“When people around here don’t know where they’re going or how to run a boat, they usually go for the Alligator Reef Lighthouse,” he says. “That’s where they’re going to shoot for because you can see it from miles and miles away.”

If Shawna was running toward the light, her course would put her some distance south of the beeline that Carlos and the Coast Guard boat were making toward the Humps. So, like a free safety sniffing an interception, Carlos broke right. Then he came to a full stop and scanned the horizon.

He knew just what he was looking for, again thanks to his local knowledge. The Freedom Boat Club where Shawna and Tony had rented their boat is just across the marina from Carlos’s slip. The club only rents Cobias and sure enough, Carlos soon spotted what looked like a 24-Cobia maybe two miles away, steering erratically. He turned the wheel and hit the throttles.

“As I’m getting closer there’s nobody on the helm, nobody answering the radio. Nothing,” Carlos recalls. “And then I saw someone on the boat, holding another person and waving one hand.”

The first thing Carlos did when he arrived on the scene was radio the Coast Guard with the vessel’s precise coordinates. Then, with the cavalry on the way, he stepped onto a boat that looked like something out of a thrasher movie.

Here again a local connection proved critical. A few years ago one of the local firefighters gave Carlos a tourniquet. He put it in his first aid kit and didn’t give it another thought until he pulled up on the 24-Cobia and saw Tony with blood spurting from his arm “like a pipe broke or something.”

This, to put it mildly, was not Carlos’ cup of tea, Ilene says. “Fun fact, he has a phobia to blood.”

“I can’t stand the sight of it,” Carlos confirms, “but I had to save this guy’s life. I put the tourniquet on and kept turning it. I was hitting him, you know, ‘Wake up, wake up. Here comes the Coast Guard. Five more minutes.’”

Moments later Carlos looked over his shoulder and the Coast Guard was there. They transferred Tony to the response boat and roared off toward the hospital, leaving Carlos and a shell-shocked Shawna on the bloodied Cobia. That’s when Ilene took charge.

“I’m at home listening to the whole situation and I call Carlos. I’m like, ‘Where’s the wife?’ and he said she’s in the boat. I go, ‘Full of blood? I’m going to send out Nelson – our son who is also a tow boat captain – and you put her on your boat and get her back to land.”

By the time they got back to Snake Creek, Tony was at nearby Mariner’s Hospital, where he was stabilized and transferred to Miami for surgery. He made a complete recovery and later told reporter Kellie Butler Farrell of Keys Weekly just how close he’d come to dying that day.

“The doc said you have six units of blood in you and they had to put three back into me, so I lost half of my blood,” he told Farrell. “Ten more minutes and I wouldn’t be here.”

Carlos didn’t call the hospital to find out what happened to Tony. “I thought I’d never see the guy again. Another tow, another rescue. Then one day I got home and Ilene was like, ‘He’s coming by with his wife.’”

When the couples met, Tony and Carlos embraced. “He gave me a hug, and she did the same. And then he said ‘Thank you Carlos for saving my life.’ And I was like, you don’t have to thank me. I just did what I had to do.”

Carlos later received the Lifesaving Award from AFRAS, the Association For Rescue At Sea, and TowBoatU.S.’s highest honor, the Woody Pollak Award. Both citations credit Carlos’s instincts and local knowledge with saving Tony’s life.

Looking back on the rescue, Carlos has advice for anyone operating a boat offshore. Number one, no one should count on a cell phone to call for help. Having a VHF radio and knowing how to report your coordinates is critical. A properly registered EPIRB or Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) is also a good idea, Ilene adds.

It’s also important to be sure more than just one person knows how to operate the boat, navigate and deal with emergencies. When Tony sliced open his arm, it was up to Shawna to make the distress call, administer first aid and get the boat back to port. Though she hadn’t prepared for any of those things, she was able to maintain her composure and call for help. That, plus Carlos’s quick thinking, was just enough to save Tony’s life – a point he was sure to make when visiting Carlos and Ilene.

“He said, ‘I thank the Coast Guard, I thank Carlos, but I thank my wife over everything because without her I wouldn’t be alive,’” Ilene says.

The U.S. Coast Guard is asking all boat owners and operators to help reduce fatalities, injuries, property damage, and associated healthcare costs related to recreational boating accidents by taking personal responsibility for their own safety and the safety of their passengers. Essential steps include: wearing a life jacket at all times and requiring passengers to do the same; never boating under the influence (BUI); successfully completing a boating safety course; and getting a Vessel Safety Check (VSC) annually from local U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, United States Power Squadrons®, or your state boating agency’s Vessel Examiners. The U.S. Coast Guard reminds all boaters to “Boat Responsibly!” For more tips on boating safety, visit uscgboating.org.